DECODED

DECODED“Would Langer still have his job were it not for the ‘Test’ documentary?” was one of the many phrases that was being floated around as a joke, in the aftermath of Australia’s 2-1 defeat to a depleted Indian side at the start of the year.

You suspect now that those sitting in the Cricket Australia headquarters would be pondering over this very statement unironically. In the wake of what has transpired over the past twelve months, only a miracle could help Langer keep his job. And that miracle, it feels, would need to be more than just the Aussies retaining the urn.

Such an upshot was unimaginable two years ago. Australia had retained the Ashes on English soil for the first time in 18 years, had considerably exceeded expectations in the World Cup and had put their name on the world cricket map once again. Langer being at the helm felt like a marriage that was meant to be.

But two years on, the honeymoon period is over and the relationship has turned toxic. Australia will enter the T20 World Cup on the back of a historical low, have more problems than positives in their Test side and are, really, only winning matches in a format no other team, of late, has been paying heed to.

Langer took over at a point where everyone unanimously felt Australian cricket had hit rock bottom, but events over the course of the last eight months have shown that there could yet be a minute possibility of the team touching a rockier bottom that is present underneath.

For Australia, the numbers under the Western Australian, despite the euphoria of Ashes 2019, don’t read pretty. Their win/loss ratio across formats, since Langer took over, is a mere 1.056 (56 wins and 53 losses), a figure worse than all but only three other sides - West Indies, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Purely statistically, these numbers in itself are a damning indictment of Langer’s time at the helm of affairs.

Yet during Langer’s tumultuous ongoing stint as the head coach of Australia - a strained relationship which hit its nether last week, with the 4-1 defeat against Bangladesh - the numbers, in many ways, have been the least of the problems.

It is what has gone on behind the scenes that has, more often than not, ensured that the team has lost matches of cricket even before it has taken to the field. A deeper delve into his series of blunders, questionable decisions, error in judgements and overhasty man management highlights the magnitude of Langer’s shortcomings and depicts how he has, essentially, apart from underachieving, also set up the team for long-term failure.

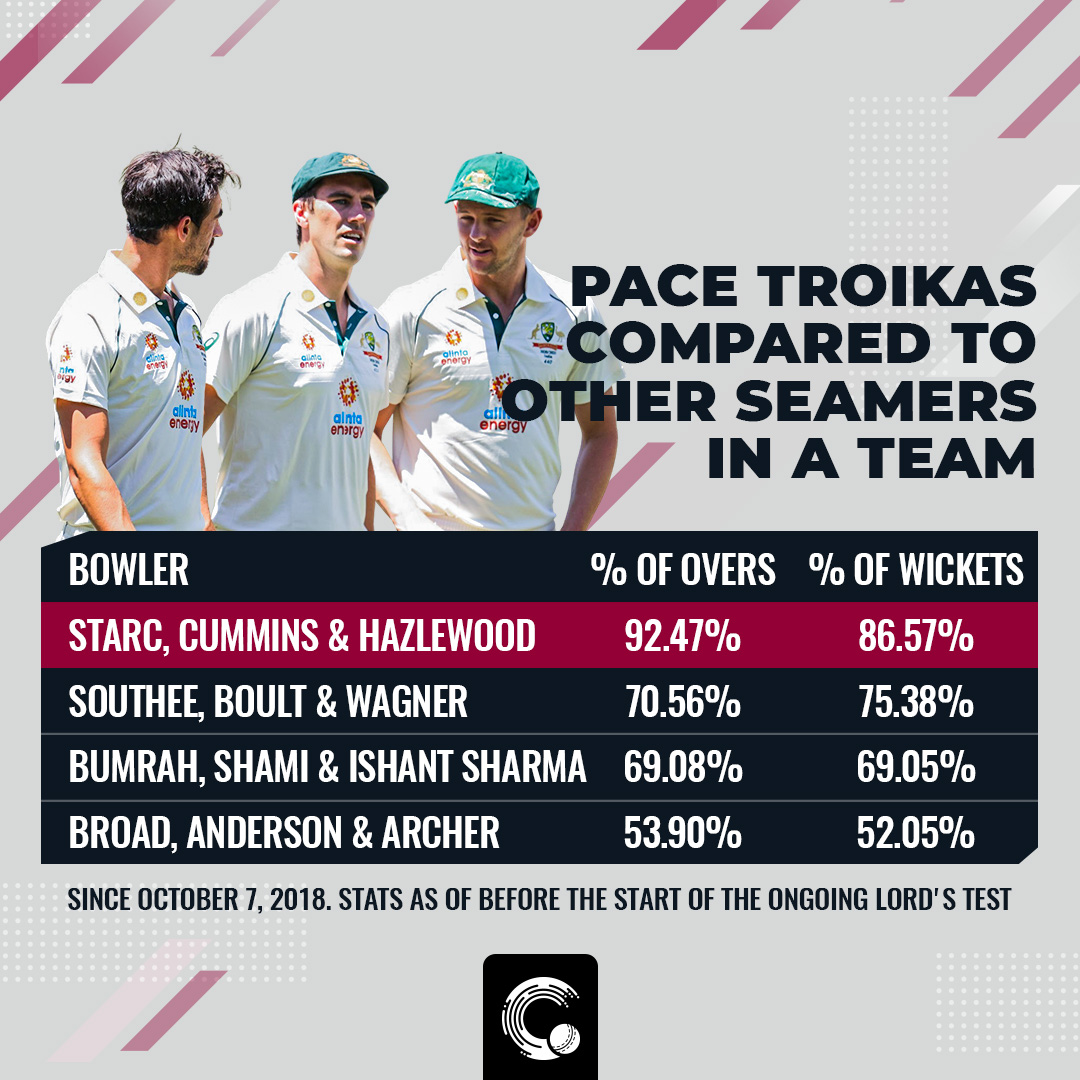

JL’s unhealthy obsession with Pace Troika

A cricket team can be considered blessed if it has two world-class seamers co-existing at the same time. In the form of Pat Cummins, Josh Hazlewood and Mitchell Starc, Australia have three. Yet what the presence of this almost-impenetrable trio has done is stop the head coach from looking elsewhere while constructing the playing XI.

Quite astonishingly, of the 2348.1 overs that have been bowled by Australian pacers in Tests since Langer took over, a staggering 1,878.5 overs have come from the arm of the three aforementioned seamers. All three of Cummins (752.1 overs), Starc (598.1 overs) and Hazlewood (537.3 overs) have sent down over 500 overs under Langer, and all three seamers feature in the ‘most overs bowled by pacers in Tests’ since October 2018 list. This despite Hazlewood playing fewer games than anyone in the Top 15 in the said list. While the ‘pick the best you have at your disposal’ sentiment is understandable, Langer’s obsession to keep fielding Cummins, Hazlewood and Starc together in every Test is proving detrimental to both the team and individuals. Not only will the three bowlers - all of whom are all-format bowlers - suffer physically, their inhumane workload will also deter their performances, with fatigue preventing them from performing at the best of their abilities.

While the ‘pick the best you have at your disposal’ sentiment is understandable, Langer’s obsession to keep fielding Cummins, Hazlewood and Starc together in every Test is proving detrimental to both the team and individuals. Not only will the three bowlers - all of whom are all-format bowlers - suffer physically, their inhumane workload will also deter their performances, with fatigue preventing them from performing at the best of their abilities.

This was pretty much the case in the Border-Gavaskar Trophy earlier this year where all three seamers - Starc, in particular - ran out of gas by the time the Gabba Test arrived. Their inability to bowl India out in the last two Tests was as much down to their own tired legs as it was to the skill of the visiting batsmen.

More importantly, however, by only fielding Cummins, Hazlewood and Starc, Australia are pretty much shooting themselves in the foot by not deepening their pace inventory in the longest format.

India, England and New Zealand have all recently flexed their strength in depth in the pace-bowling department, and have showcased the benefit of doing so, and yet Australia, despite boasting a fine talent pool, have only an injury-prone James Pattinson who is ready to slot in. That Michael Neser, by some distance the most Test-match-ready seamer in Australia, still remains uncapped pretty much typifies Langer’s reluctance to rest the incumbents.

Easing newcomers into the side alongside seniors and giving them Test match experience will ultimately benefit both the team and the individual, but Langer’s myopic approach could potentially leave Australia in an uncomfortable position should they find themselves at the receiving end of bad luck.

Unjustifiable alienation of Usman Khawaja from white-ball cricket

As India tamed Joe Burns, Marcus Harris and Matthew Wade eight months ago, whilst barely breaking a sweat, fans and sections of the media clamoured for the recall of Usman Khawaja. The Australian management, though, did not give in. And they were justified in doing so.

Unlike any of his competitors, Khawaja, despite having ample Test experience, was unable to buy a run in Shield cricket: the season after he was dropped from the Test side, Khawaja averaged a mere 18.36 across 11 Shield innings. So though he eventually struck a ton days before the squad for the first Test was announced, it simply was not enough to wipe out a year of abject failure.

What has not been justifiable - and continues to be flabbergasting, to this very date - is the inexplicable and unjustifiable alienation of Khawaja from white-ball cricket. In 2019, the southpaw was one among just six batsmen to score over 1,000 ODI runs in the calendar year.

His penultimate knock that year (which was also the last ‘fully fit’ ODI knock he played in 2019, given he blew his hamstring after that) was a match-winning 88 against New Zealand in the World Cup at Lord’s where, from 92/5, he helped his side post a respectable 243/9, a score that ultimately proved to be match-winning. Two years on, the 88 against the Kiwis still remains Khawaja’s penultimate knock in ODI cricket.

It is not like he failed to rack up the runs post his axing. In the 2019/20 Marsh Cup, Khawaja finished as the fourth-highest run getter, with 398 runs @ 79.60. The season after, he averaged 43.50, striking two fifties in 4 innings. Yet Langer & Co. made up their minds to completely move on from Khawaja, often citing ‘age’ as the reason for doing so.

Such a statement reeks of hypocrisy, though, as, quite ironically, all of Dan Christian, Moises Henriques and Matthew Wade - who featured in the tours of Bangladesh and West Indies - are all either of the same age or older than Khawaja. The 34-year-old was not taken to the Caribbean and Bangladesh despite there being a clear paucity of senior batsmen. Far too often the goalposts have been shifted by the management to suit their narrative.

Ultimately, however, it is Australia - and not Khawaja - who have suffered. Had the 34-year-old not been frozen out of the side unceremoniously, the Kangaroos, in the last two tours, would have had not just a world-class top-order batsman - who is adept at playing spin - at their disposal, but a leader too.

And though it is true that a bulk of his run scoring have come in the domestic 50-over competition, Khawaja, through his showing for Islamabad in PSL 2021 - 246 runs @ 49.20 and SR 152.79 - showed how much of an asset he could be in the shortest format, particularly in the sub-continent. And you suspect, whilst chasing those 120-something targets against the Tigers, they would have loved to have a batsman of Khawaja’s calibre and experience in the side. It is worth remembering that, five years ago, it was Khawaja who ended T20WC 2016 as Australia’s top-scorer.

Only Langer knows why he completely alienated Khawaja, and if there are cricketing reasons behind it, the world would love to know.

Unrest within the dressing room

Sticking with Khawaja, then, one of the most popular clips from ‘The Test’ documentary was his brutally honest conversation with Langer, where he said the following:

“I think the boys are intimidated by you. There’s a bit of that walking on eggshells sort of thing. I feel like the boys are afraid to say it.”

Skipper Tim Paine alluded to it: “I know you won’t agree but they feel they want just a little bit more positivity. They think they know now what they are doing wrong but at times they feel they are going out in the middle worrying too much about that. Just a slightly more positive message around batting at times.”

Two years on, one cannot help but feel that these words foreshadowed what was to follow in the months that followed - a complete dressing room unrest which allegedly resulted in CA, in the end-of-the-season review, requesting Langer to ‘change his coaching style to continue’.

Langer, by nature, is an intense personality. Perhaps the closest coach there is to a school principal. And his strictness, it felt, was what Australia needed post the Sandpaper gate. But there is a fine line between being strict and unrelentingly unmerciful. And Langer, by the players’ own admission, seems to have crossed it without his own knowledge.

Until earlier this year, clips in ‘The Test’ remained the only evidence of Langer’s somewhat strained relationship with the players. But all hell broke loose in the aftermath of the India series. Players first leaked the Sandwich-gate (involving Labuschagne) to the media and then also willingly leaked a Text message from JL that specifically asked them to not talk to the media.

“Some senior players are frustrated at the atmosphere in the team being brought down by the coach’s shifting emotions and what they see as too much micro-management. They say that has extended to bowlers being bombarded with statistics and instructions about where to bowl at lunch breaks including during the fourth and final Test against India at the Gabba,” an smh.com.au report revealed.

More players started talking to journalists off-record and ‘The Grade Cricketer’ podcast revealed that some players described the dressing-room atmosphere as ‘toxic’ and ‘way worse than expected’. It was also revealed in the podcast that the players feared that the whole JL saga would end up being a ‘slow car-crash’ (wherein the situation would drag out for an excruciatingly long period). The leaks were also believed to have come from ‘multiple players’. Given it’s only Smith, Paine and Finch who have publicly thrown their weight behind Langer, such a claim cannot be dismissed.

Which is precisely why recent happenings in Bangladesh - where Langer was allegedly involved in a heated altercation with a CA staffer over a video - raise serious suspicions that there might be an actual dressing room unrest. Again, according to a smh.com.au report, “the incidents were witnessed by at least a dozen people and left some players taken aback and with a sense of unease about what had transpired.”

Perhaps the truth will never be out. Or it will be out only years from now. But with Australia already suffering enough on the field, the last thing they’d want, you suspect, is a toxic relationship between the coach and the players, with a T20 World Cup and a home Ashes coming up.

Short-sighted and panic-stricken decision making

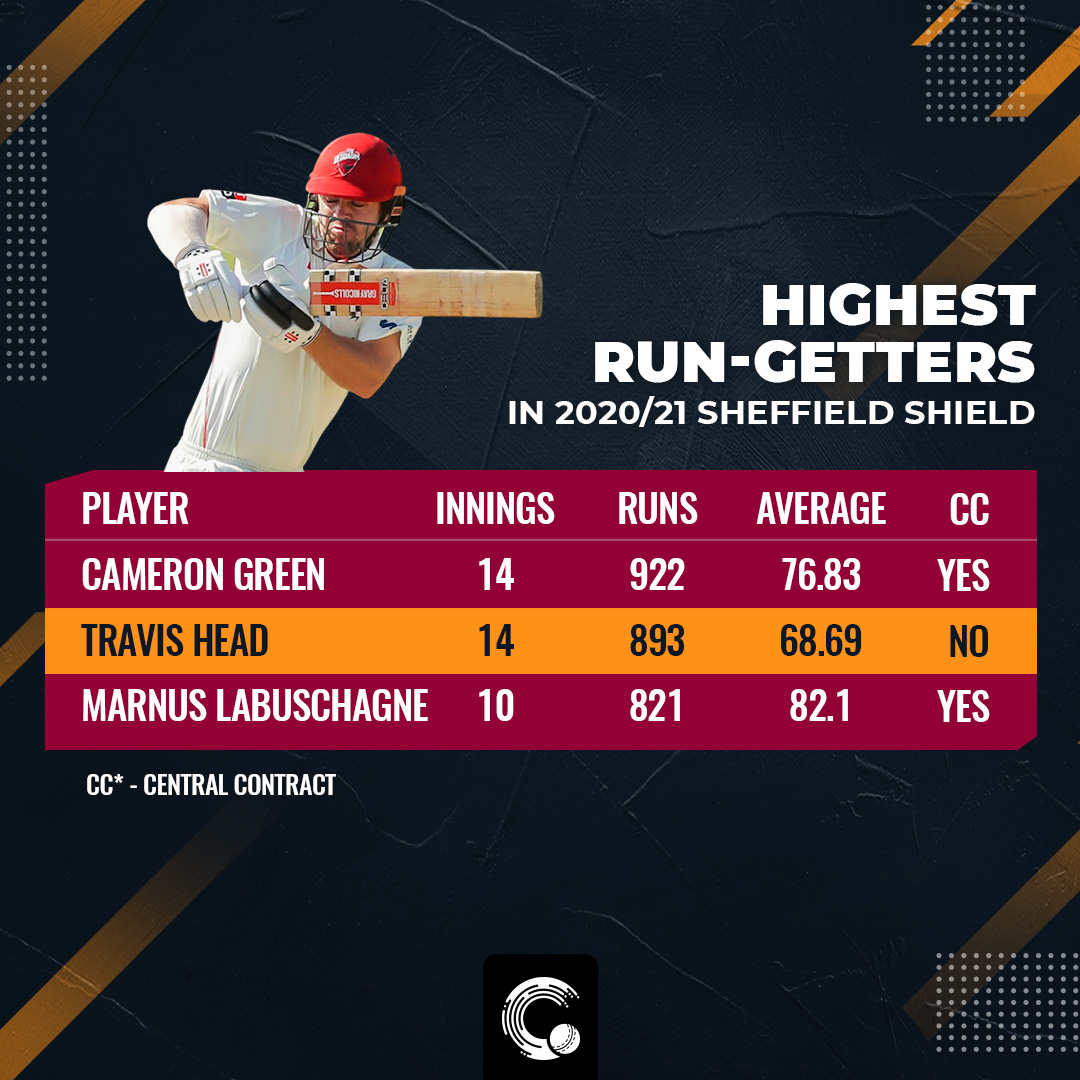

In January 2019, Travis Head (South Australia captain) was promoted to the post of vice-captain of the Australian Test side, with the vision of him being one of the candidates who could potentially take the mantle over from Tim Paine. Fast-forward to August 2021, Head, still only 27, is no longer a centrally contracted Australian player.

His fault? Failing twice against India across two matches in which no specialist Aussie batsman, not even Steve Smith, racked up the runs. That he’d scored a 171* and 151 for South Australia in lead-up to those two Tests did not matter. Nor did the fact that he’d bagged the MOTM award three Tests before getting axed.

Not offering Head, a former vice-captain, a central contract - despite him finishing the 2020/21 Shield season as the second highest run-getter - is the kind of decision that, really, is emblematic of Langer’s decision-making during his time at the helm: panic-stricken, myopic and short-sighted.

This questionable decision-making - which also extends to tactics - was also on full display during the last two T20I tours, which Australia lost with a combined scoreline of 2-8. Deemed as preparation for the T20WC, how Australia approached the T20Is against West Indies and Bangladesh was anything but that.

This questionable decision-making - which also extends to tactics - was also on full display during the last two T20I tours, which Australia lost with a combined scoreline of 2-8. Deemed as preparation for the T20WC, how Australia approached the T20Is against West Indies and Bangladesh was anything but that.

While the Mitchell Marsh promotion clicked - and in turn was lauded as a masterstroke - it was again a move that had little long-term thinking behind it. Where will Marsh bat if indeed Smith makes it to the T20WC squad? And should Smith indeed not make it, where is the merit in taking a six-hitter like Mitchell Marsh away from a weak middle-order lacking finishers, and fitting him in a top-order that is already stacked?

And, why did Wade open in 4 of the 5 T20Is against the Windies (when Finch was still fit) when he would, in all likelihood, assuming both Finch and Warner play, be needed to bat in the middle-order come the T20WC?

The younger players in the tour, too, were mismanaged grossly. While Ben McDermott, a top-order batsman, was shifted up and down the order (he began at #6, before being pushed to open, and then was slotted in at #4), Josh Philippe, the most prolific young batsman in the Big Bash League across the last two seasons, featured in only 6 of the 10 games.

He, too, was initially slotted-in at No.4, a position he’d never previously batted in, in T20 cricket. In contrast, a 34-year-old Moises Henriques not only played all 10 matches - the same as Philippe and McDermott combined - but did so in his preferred position in the middle-order.

Essentially, through some grotesque decision making, Langer has ensured that Australia will enter the T20WC not knowing what their batting order, barring Maxwell and Warner, will look like. By no means will it be a first, though, for such uncertainty has almost been a trademark of the Western Australian’s three-year tenure.