ANALYSIS

ANALYSIS“If I fast forward it, the Indian tour against India, the Test tour in three or four years’ time, to me that’s the ultimate. We will judge ourselves as a great cricket team if we beat India in India.”

It is unusual for Australian or English cricketers to mark some other assignment as pivotal. But Justin Langer meant what he said after Australia retained the Ashes with him as the Head Coach. Langer was part of one of the only two sides that have beaten India in India in the past twenty years.

Both players or the viewers belonging to Gen Z will not know of a tougher assignment. It was late in 2012 when England - with an over-my-dead-body opener, a tamer of the turning ball in the middle-order and two spinners in their prime countering for every requirement - did the unthinkable. And since then, India have renovated the fort to make it impenetrable.

Out of the 39 Tests at home since 2013, India have won 31. These have come across 13 completed series, all won by India. Both Australia and England did manage to start a tour with a win but India managed to claw their way back to remain unconquered all this while.

Let alone losing, 13 of these victories have been by an innings, the other 10 by 100 + runs and five by 8 wickets+. The opposition have hardly had a sniff. India’s win/loss ratio in this period has been a spectacular 15.5.

In the last four years, India have not just been a home track bully. Their achievements overseas have brought them closer to occupying the revered space created by the West Indies of the 80s and Australia of around the 2000s. While being dominant everywhere they have played, the West Indies in the 80s (win-loss ratio of 18) and Australia from 1998 to 2007 (win-loss ratio of 15.7) were as dominant if not more as what India are in their backyard.

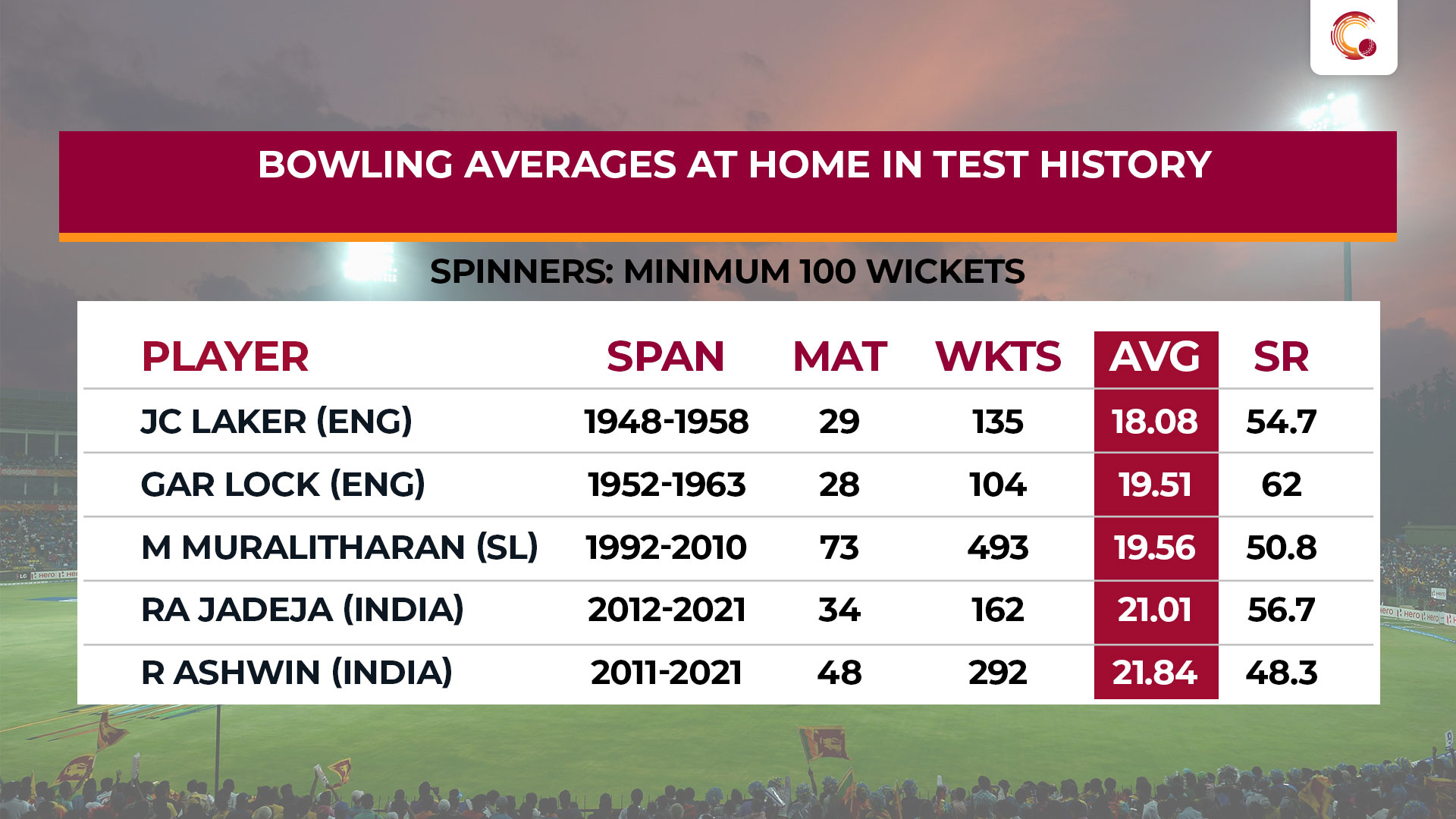

Arriving at the primary reason for India’s home dominance is not a brain teaser. India have not one but two spinners who find themselves in the pantheon of best spinners of all time in terms of exploiting the home conditions.

But the hallmark of India’s success is not spin alone. While the absence of an ICC trophy might tarnish the legacy of the Kohli-Shastri era, no other captain-coach combo had such a defining impact for India on the Test front since after the early 70s. The weapon that they nurtured to ensure India’s supremacy in Tests was something that was obvious all along but never really came to fruition before 2018. This was pace bowling. “We had a wish that we could take the pitch out of the equation.” This much-quoted line from Shastri sort of became the motto of the team.

But the hallmark of India’s success is not spin alone. While the absence of an ICC trophy might tarnish the legacy of the Kohli-Shastri era, no other captain-coach combo had such a defining impact for India on the Test front since after the early 70s. The weapon that they nurtured to ensure India’s supremacy in Tests was something that was obvious all along but never really came to fruition before 2018. This was pace bowling. “We had a wish that we could take the pitch out of the equation.” This much-quoted line from Shastri sort of became the motto of the team.

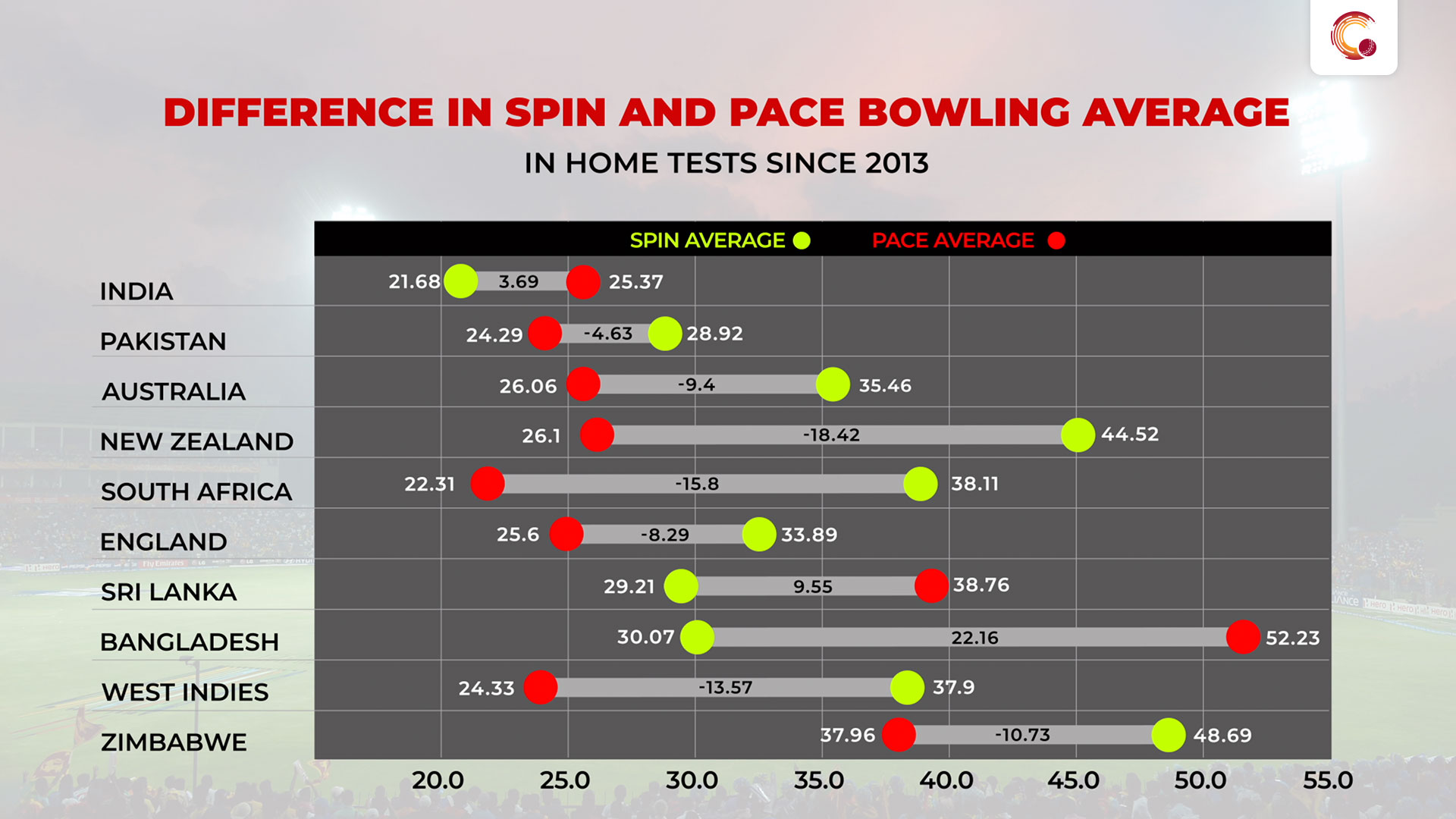

What was the impact? While Indian spinners were miles ahead of all the Test-playing nations in terms of bowling average, their pacers were not far behind. And thus the difference between the bowling average between pacers and spinners in home conditions has been the least for India since 2013.

Talking about the Indian pacers, Mohammed Shami and Umesh Yadav have a bowling average of 15.04 and 15.27 at home respectively. The only better to do better than the duo in his home conditions is Kyle Jamieson (13.27). Shami and Umesh perfected the art of bowling on the Indian wickets, keeping the ball in the channel, targeting the stumps often, thus bringing all modes of dismissals into play. A strategy that the Indian pacers replicated in Australia during the recent tour as well.

And before we get a feeling that all this success is because of the bowlers, there is something we should know. The definition of an ideal all-rounder has always been to have as much of a difference as possible between their batting and bowling averages. On this parameter as well, India have been the best all-round side at home with a difference of 18.75 between bat and ball since 2013.

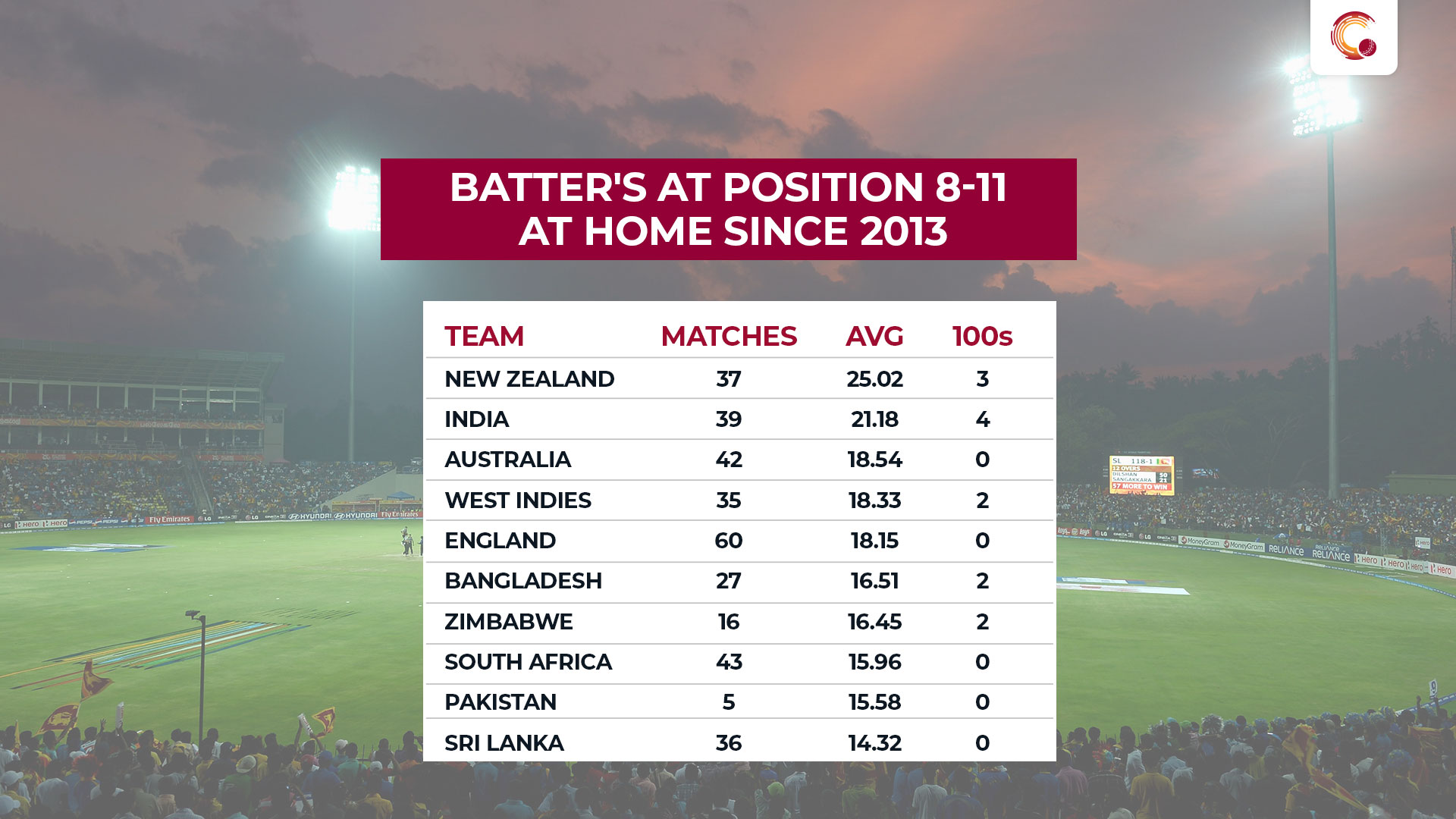

While this speaks volumes about the potential of India's batsmen at home, it also points towards a possibility of lack of effectiveness of opposition bowlers in the Indian conditions. Lastly and perhaps an important aspect that has often gone under the radar. If there is one thing that has haunted India across formats is the ability of their tail-enders to contribute when needed. The difference that the lower-order runs can make was for everyone to see in the second Test at Lord’s in August when Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Shami shocked England. However, at home, crucial lower-order runs have not been a problem for India.

Since 2013, Indian batters at positions eight to eleven have averaged the second-best in home conditions after those from New Zealand. And thanks to an ex-Tamil Nadu opener who goes by the name of Ravichandran Ashwin, the Indian lower-order have more Test centuries at home than the Kiwis.

With plenty of players in their prime and still young enough to last atleast half a decade, India’s juggernaut looks set to continue. Until someday, when a team can put together a squad of great cricketers who can counter everything India throws at them at their home to win the ultimate prize in the Test arena.