ANALYSIS

ANALYSIS“Our Shakib Our Dream” read a placard when Shakib Al Hasan walked out to bat against England in the ongoing T20 World Cup. The unanimous admiration that Shakib receives in Bangladesh sits at par if not more than any other sportsperson has enjoyed among the fans of the team they have played for. And it makes sense. He is hands down the most important cog in their wheel.

Just two years ago, Shakib single-handedly kept Bangladesh competitive in the 2019 World Cup. And if being good-natured and universally likeable were not the criteria, Shakib would have pipped Kane Williamson for the Man of the Tournament award too. Shakib has been the man of the match in every game that Bangladesh have won in T20 World Cups. This piece of trivia is enough to signify his importance for Bangladesh cricket.

If hypothetically, Shakib is not able to bowl due to an injury and his batting numbers take a hit due to a bad run of form, Bangladesh will find themselves in a soup. The eyes of the media will follow him around and whenever someone from the team meets the press, he will have to face questions about Shakib. For India, something similar has happened around Hardik Pandya.

Hardik’s bowling fitness has been at the crux of media attention, debates and discussions ever since he underwent a back surgery in October 2019. He has not bowled a single over for Mumbai Indians across two seasons since. He chipped in for India first against England in March 2021 and against Sri Lanka in July this year. But, question marks on his ability to bowl even cost him his place in the Test side during the long tour of England from June to September.

During the current IPL, the Mumbai Indians kept everyone interested by slipping in that Hardik could bowl at some stage. But when he did not roll his arm over during the warm-up games before the Super 12s began and in the nets ahead of the clash against Pakistan, it was evident that Hardik will not be bowling anytime soon.

In the middle of a weeklong break before India’s second game, against New Zealand, Hardik turned up for a net session spending some time on both facets of the game. As if India’s campaign in the World Cup relies on whether Hardik could bowl or not, the media-verse got in a frenzy with the development. The host broadcaster even had the visuals of Hardik bowling in the nets running on the screen while Afghanistan were playing Scotland.

The surveillance that Hardik is under seems bizarre given that even if he is able to bowl in the next game, he is India’s sixth bowling option. In the 2000s when the Indian cricket team finally moved on from being a one-man side, even the mandatory fifth-bowling option used to be a makeshift arrangement. India had Joginder Sharma in 2007 and Yuvraj Singh to do the job in 2011. A complete all-rounder like Ravindra Jadeja would have been a luxury then.

But, what contributed significantly to a successful campaign in the two tournaments then were RP Singh and Zaheer Khan respectively who specialized in the skill required with the new ball to give India early wickets. If India are to go all the way in the ongoing tournament, an issue that should be the actual headache for India are the returns of their new-ball bowlers in the Powerplay, not just in the game against Pakistan but since the start of the year 2020.

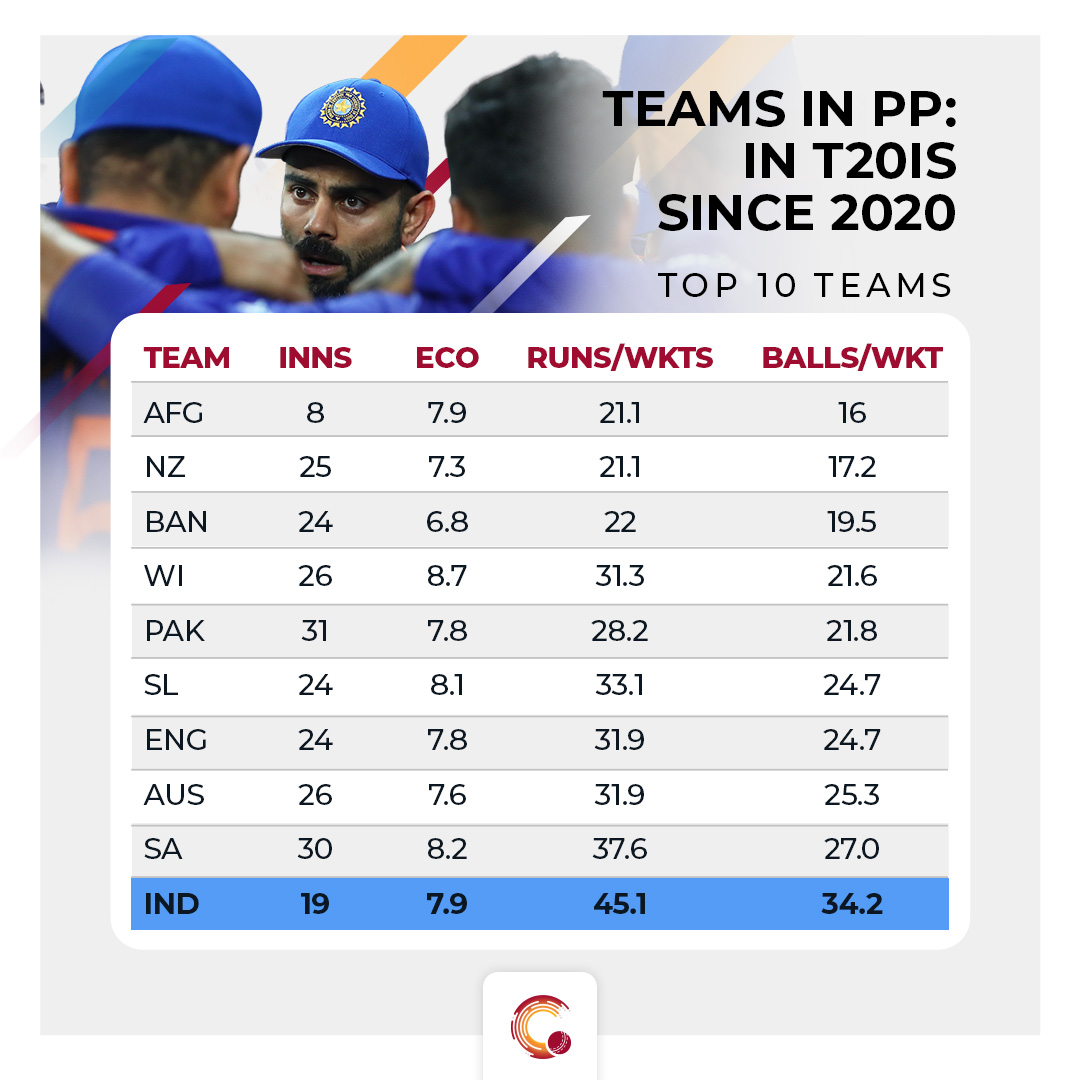

In the last two years, Indian bowlers in the Powerplay have been collectively worst by some distance than all other top-10 ranked nations. They have averaged only about one wicket per game in the first six overs in 19 games since. While averages can be misleading at times, this is a fair representation of the lack of wickets for India upfront given that in the last 12 T20Is, they could not take a wicket in the Powerplay thrice and could pick only one in the other nine.

Spinners, bowling in the first six overs, have saved these figures from looking even worse to an extent. Which they are at 42.5 balls per wicket in the Powerplay for Indian pacers. This implies not even a single wicket in this phase. And it is not just a T20 phenomenon. Even in ODIs, India have a balls per wicket record of a staggering 112.5 balls per wicket in the Powerplay (first 10 overs). This is more than two times the next worst side (South Africa: 49.4)

Coming back to the game against Pakistan, Shaheen Shah Afridi bowled a near-perfect first over and yorked out Rohit Sharma. When it was India’s turn with the ball, Bhuvneshwar Kumar began with a gentle medium pace devoid of any movement. Mohammed Rizwan flicked and pulled with ease. Afridi rocked India further in his second over whereas Bhuvneshwar’s figures in the Powerplay read two overs for 18 at an average speed of a mere 125 KMPH.

India have mixed and matched their selection approach for the World Cup. For spin, they went for freshness over the incumbents. In the pace department, selection criteria seems almost fixedly skewed towards experience. Jasprit Bumrah was always going to be in the first XI. But, his role is to be an all-phase bowler with his quota of overs separated in a spell of 1+1+2 across the three phases. What India needed in the pace department was someone to share the burden with the new ball in a phase where taking wickets is of elite importance.

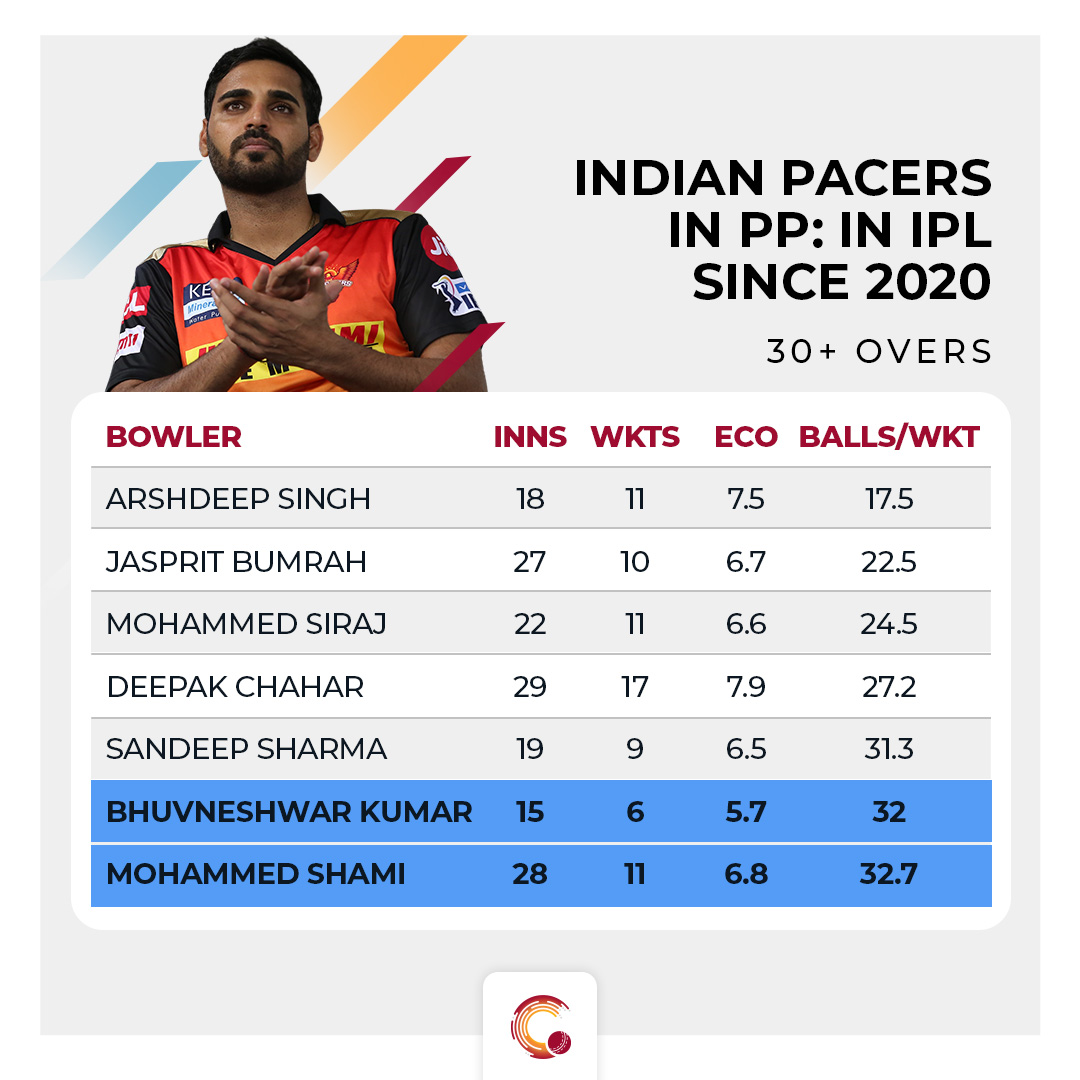

But the two pacers India chose to support Bumrah were more on reputation than numbers. In the last two seasons of the IPL, Bhuvneshwar has bowled 32 overs. There are seven Indian bowlers who have bowled as many overs or more. Both Bhuvneshwar and Mohammed Shami have the lowest balls per wicket record in the Powerplay among those seven.

Then there are other pacers like Avesh Khan (23 balls per wicket) and Shardul Thakur (16.3 balls per wicket) who have done better than Bhuvneshwar-Shami duo in this phase but have bowled fewer overs. The duo has bowled 24% of the overs (27 out of 114) for India in the first six overs of T20Is since 2020. Bhuvneshwar has returned with four wickets in 17 overs and Shami none in 10.

Since the loss against Pakistan, the arguments outside Hardik Pandya have been around how India’s batting approach could have been more aggressive. But with no wickets upfront, the result would have been the same had India added 25 more runs to their total.

This does not imply that having a bowling-fit Hardik will not be a value add. It will allow India to experiment with other combinations. It can give them the option to target the balance of three pacers and three spinners. However, unlike other sides, India do not necessarily need a sixth option. Pakistan might need Mohammad Hafeez as a sixth option since both their other spinners turn the ball in the same direction. This is not the case with India. What India need more importantly is someone to lay the groundwork for Bumrah like how Afridi does for Haris Rauf or Chris Woakes for Tymal Mills.

Since the start of 2019, only seven batsmen with 600 or more balls faced in T20 cricket have a balls per six record of less than 10. Hardik is one of them, third on the list with that number at 8.9 balls per six. No other Indian is at 14 balls per six or below. He is the only finisher India have cultivated over the years. Bowling or not, India need Hardik in the team. But, he is not India’s Shakib Al Hasan. The responsibility of India’s underperformance with the ball should not fall on his shoulders or his lower back.