News

Decoded: What set Steyn apart from the rest?

DECODED

DECODEDIf you are creating the perfect bowler to execute reverse swing in a lab, Dale Steyn is what you might come up with

Fast bowling is tough. From a distance, it looks cool. But former cricketers, Shoaib Akhtar and Jeff Thomson to name a few, have stated one needs to be mad to take up fast bowling. It comes with the relentless toil of running in, loading your body in the delivery stride, bending your back, rolling your arm over and going through the complex movements of your follow through, all of it, again and again, and again.

On top of it, when the conditions don’t offer them much, the game just seems unfair to them. This is often the case in Asia where the strive for domination fluctuates between the batsmen and the spinners. The pacers don’t matter much on the dusty tracks found there.

When Dale Steyn announced his retirement at the end of August 2021, social media went into a frenzy acknowledging his status as the best bowler of the millennial generation. Stats were thrown left, right and centre. Some talked about his strike-rate - a wicket every seven overs, some mentioned the number of days he spent at the pinnacle of Test bowling rankings - nearly six years, but the most common notion discussed was his record in Asia.

He has most wickets in Asia by a non-Asia seamer (92). The next best on the list is Courtney Walsh with 77 scalps. He has the most wickets in wins in Asia by a non-Asian seamer (52) which speaks about his impact. He is the only non-Asian seamer with five-wicket hauls in three different Asian countries - India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan.

How did Steyn topple the unattainable land for a seamer? The answer lies in two words - reverse swing. It swings the other way, it swings late, almost in a blind spot for the batsman, giving batsmen little to no time to adjust to the change in trajectory. Waqar Younis, a top-notch exponent of reverse swing, deemed it as a necessity for any side in a conversation with Mark Nicholas in 2016. In a recent example, it was this precise art that helped Jasprit Bumrah to swing the game in India’s favor in the Oval Test.

****

If you are creating the perfect bowler to execute reverse swing in a lab, Dale Steyn is what you might come up with. Even one of his shortcomings as a fast bowler, a substandard height of 5 feet 10 inches for a pacer, fell perfectly in place to reverse the ball. Coupling it with his whippy action, he became a skiddy customer to deal with. The change in action was, in fact, so subtle with Steyn, it was impossible for the batsmen to spot it in the split second he rolled his arm over.

“You need to have serious pace because without it, you are not going to beat the pace,” stressed Younis while talking to Nicholas. This is what Bumrah did at the Oval. This is what Younis himself did, at the Oval, twice in the 90s. This is what one thing Steyn had himself focussed on in his preparation to the Test series in India in 2010. "You're not going to get a lot of sideways movement off the wicket but a ball bowled at 145k, whether it's in Jo'burg or Nagpur, is still 145ks in the air. The plan was to hit the deck hard, with pace,” said Steyn after his career best figures of 7 for 51 in Nagpur. AB de Villiers later described it as the flattest track he has played on.

Pace has never been a problem with Steyn. After his 7 for 51, Sunil Gavaskar described his outswingers as good as those of Kapil Dev but only 10 kph faster.

However, like the game of cricket, bringing out reverse swing is also a team effort. Steyn had the support of Paul Harris, the left-arm spinner, who would pitch the ball consistently in the rough produced by the right-arm seamers at the other end and scruff the ball up. It is the same job that Ravindra Jadeja did for Bumrah at the Oval.

****

You add control to all these factors which Steyn had in plenty as his career progressed. Even a strenuous skillset like fast bowling demands mental proficiency and discipline and it is underlined by the contrast in Steyn’s first two trips to Sri Lanka.

Steyn didn’t have the most auspicious start to his time in Asia. In his first Test, he was a part of the Protea attack that went through the languish of the highest Test partnership partnership, a 624-run stand between Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene. He got Sangakkara out early, when the left-hander was on 12, but it was a no-ball. Steyn’s figures that innings read 3 for 129 in 26 overs (economy of 4.96). In the next Test, he picked a five-wicket haul but South Africa lost by 1 wicket.

His next trip to the island nation was eight years later, in 2014. "I thought I was absolutely useless back then," said Steyn after his 5 for 54 blew out Sri Lanka in the first innings of the Galle Test in 2014. "I was just bowling as quickly as I could. Now there is a lot more thinking and planning that's involved,” he concluded, clearly stating that he has become older and wiser in the meantime.

Using his pace effectively was another aspect of Steyn’s judicious approach to fast bowling. Rather than going for the tempting 150 kph mark, he mostly operated in the 140 range which was just enough to make the batsmen’s stay difficult. Thus, he was conserving his energy for longer and impactful spells.

Using his pace effectively was another aspect of Steyn’s judicious approach to fast bowling. Rather than going for the tempting 150 kph mark, he mostly operated in the 140 range which was just enough to make the batsmen’s stay difficult. Thus, he was conserving his energy for longer and impactful spells.

He was also street smart in working the batsman over. Talking about his method to get rid of Murali Vijay, the first of his 7-wicket haul in Nagpur, Steyn said, “I worked Vijay out quite nicely with two balls that went away and then brought one back in which he left. We really planned it."

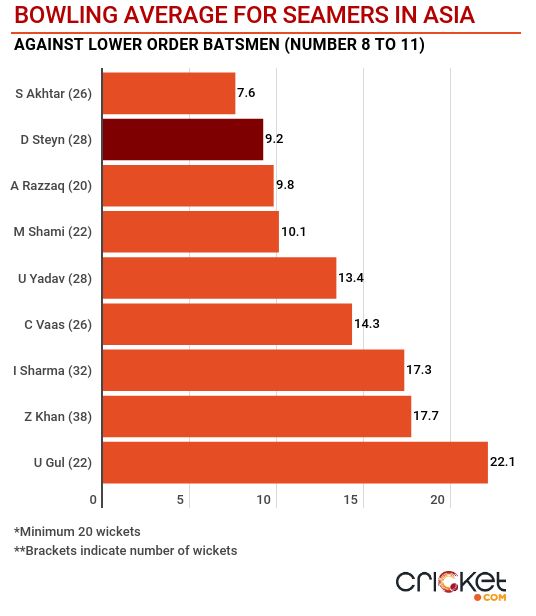

Vijay was out shouldering arms. That, however, was with the new ball. Steyn repeated it to Wridhimann Saha with the older ball. The two deliveries underlined his mastery with both the new ball for conventional swing and the old ball for reverse swing.  After the hard yards, Steyn was brilliant in running through the tail. Going back to his Nagpur heroics for one final time, Steyn returning for his final spell in the first innings, knocked out the last five Indian wickets to claim a 7-for. That spell read 3.4-2-3-5. Only Shoaib Akhtar had a lesser average against the tail-enders.

After the hard yards, Steyn was brilliant in running through the tail. Going back to his Nagpur heroics for one final time, Steyn returning for his final spell in the first innings, knocked out the last five Indian wickets to claim a 7-for. That spell read 3.4-2-3-5. Only Shoaib Akhtar had a lesser average against the tail-enders.

You can loosely call it statpadding but overall, only 30 percent of Steyn’s scalps in Asia comprised of tail-enders. He was so good against the specialist batters that those in the lower-order had little chance to circumvent his reverse swing. Moreover, it was one less thing to worry about for his captain, Graeme Smith.

The height, the action, the pace, the brain, the teammates and the control, Steyn had it all to make the ball interact with the air like no other pacer could.